Stronger

When we exercise in a meaningful way, we send a clear signal through the nervous system that we want to be able to do more. Our body responds during the recovery process by growing more muscle and vascular tissue to accommodate our demand.

That much has been acknowledged, if intuitively, for centuries; yet to this day, is only partially explained by science. “More research is needed” is the standard refrain.

Regarding strength training in gyms, theories abound, making money for some and leaving everyone else confused.

And it’s been this way for a long time.

“Hundreds of letters reach me daily” wrote Eugene Sandow in 1897, “asking ‘Can I become strong?”

At 27 years of age, the Prussian born athlete had legitimately earned the title, “Strongest Man in The World.” Among his many performance stunts was supporting three adult horses on his back and deadlifting a 1000 lb. block of granite. His demonstrations of strength were astounding, bordering on the supernatural.

He claimed to reveal the secret for obtaining strength in several books and pamphlets.

“Yes, you can become strong if you have the will and use it in the right direction. But in the first place, you must learn to exercise your mind. This first of all lesson in physical training is of the utmost importance.”

While intriguing, it is unlikely that such statements convinced many people, then or now. The more likely response was suspicion that the “true” secret was being withheld. For there was no doubt by anyone who had witnessed a Sandow performance that a secret did exist, and that it was real.

Yet Sandow may not have been concealing anything. He may have been trying to describe his firsthand experience in the most authentic way he could. The mystery was that he could not convince his own fans who wanted so fervently to “become strong.”

How many people today would like to be stronger in theory, yet can’t find a practical way to attain it? And is this caused by a lack of willpower or a lack of knowledge?

Sandow was only trying to explain something that he was intimately familiar with. But the information he offered was considered to be either too simplistic to be taken seriously, or too esoteric to be understood in the popular sense.

It’s usually assumed that Sandow lifted weights to build his strength. But the weights he brandished for publicity were light; and the weights he advised for his students were also light.

Even though light weights may be used effectively to build strength when handled with knowledge, weightlifting still may not have been the ideal methodology for the strongest man in the world.

On the other hand, Sandow regularly engaged in challenging public demonstrations of his strength. This was more likely to have been his actual strengthening regimen, even though he never identified it as such.

As far as we’re concerned, Sandow’s performances in themselves were clearly his primary exercise because he frequently and consistently held static poses with his muscles loaded to capacity.

In other words, the Sandow workout was fundamentally isometric. That is, his muscles contracted forcibly with little-to-no bodily movement.

The additional fact that the performances were brief makes our theory even more plausible because they perfectly describe what we now know to be high intensity exercise.

Those claiming that weightlifting was Sandow’s vehicle for strengthening would have to show how weights could possibly have been an effective stimulus for him, given his extraordinary status of strength.

They would also ignore the neurological law of “specificity” which states that training must mimic the objective. In our view, static exercise mimics Sandow’s performance objective whereas weightlifting does not.

Libraries are filled with volumes about weightlifting because it is the preferred method of strength training worldwide. Therefore, there is a great bias in the assertion that weightlifting is the best form of exercise for strength.

But unless one likes it as a hobby, weightlifting is not only time-consuming but possibly counterproductive – if your primary goal is to be the strongest that you can be.

Strengthening oneself does not need a complicated or drawn-out program. However, it demands knowledge, the will, and the patience.

Unfortunately, these are not qualities most people share. It is probably for this reason that Sandow had minimal success disclosing his secret to the public.

And it is also for the same reason that so many people today are lost when it comes to gaining strength, their natural birthright.

THE KNOWLEDGE

Once someone gains even a basic understanding of how skeletal muscles are made to function, the pursuit of strength can begin with confidence.

Anatomy and biology textbooks have limited use in terms of exercise, except to enable us to appreciate the immense, almost infinite, complexity of the neural, biological, chemical and mechanical systems that converge to produce energy and force in the human body.

Realizing how such a fantastic apparatus is ours to command should empower us. But this is not how exercise is viewed. It is usually presented from the outside in rather than from the inside out, which disempowers the individual and makes one dependent on external devices – such as weights for example.

The external orientation to exercise also fits the prevailing sports-centric paradigm that views all forms of fitness as a competition. It is the us against them mentality that turns barbells and dumbbells into opponents that must be overcome by brute force.

A good example of that today are those who perform weightlifting as if they are power lifting. Ideally, weights are tools to be used for acquiring strength. Powerlifting is a sport. The two types of lifting are not in the same category as they are not intended for the same purpose. Yet too many people are power lifting with the mistaken belief that they are training for strength when in fact they are merely becoming adept at “powering.”

Such activity is fundamentally counterproductive to building strength because such “sport” lifting serves our natural instinct to avoid too much effort by finding an easier way.

This is what Sandow meant when he described a typical laborer who uses his muscles every day without gaining appreciable increase in strength. [Because] “he has to get through a given amount of work, and his method is purely mechanical.”

A barbell or dumbbell is a tool, fabricated to provide a point of gravity so that muscles will be encouraged to contract against resistance. But weightlifting is no more than physical labor unless the tool is used specifically to load the muscles.

“Loading” means to contract the musculature slowly and methodically. It means to purposely increase the difficulty and effort rather than find the easiest way to move a weight, as would be the example of a laborer who is just wanting to finish a job.

Although the laborer may be exhausted at the end of the day, he has managed to get through the toil by not overfatiguing his muscles. For there is a difference between overall exhaustion and muscular fatigue that is specific to increasing strength by an appropriate method. “Exercise” is an artificial activity really designed to effectively weaken us first so that our natural adaptive responses will work to make us stronger.

Of course, this is counterintuitive for most people and, for that reason, a primary cause of personal failure. Having the correct knowledge would prevent this.

“Exercise, indeed, without using the mind in conjunction with it, is of no use.”

This is not as esoteric as it may have sounded to people in the 19th Century, because it refers to what science now describes as our neurology and the way in which the brain sends impulses to the skeletal muscles. We have a mental notion followed instantly by the action. We visualize picking up a cup and our arm and hand respond almost before the thought has had time to complete itself.

Most of the time we do this unconsciously, taking it for granted. But we can also use this power in a purposeful way.

If we can think of a muscle, we can also make it contract. We don’t need to lift or push something to activate it. We are potentially capable of doing this volitionally with or without resistance, and with just a notion about where the muscle might be located.

“…whilst the effect of weight lifting is to contract the muscles, the same effect is produced by merely contracting the muscles without lifting the weight.”

With practice, it becomes easier to exert a greater response as nerve and muscle connections become accustomed to receiving the mental message.

What’s significant here is that we can volitionally load our muscles with greater control and potentially more force than what can be invoked by lifting weights.

Volitional muscular contraction is the application of internal processes that are entirely within our mental control. In contrast, moving a weight is dependent on sensory defensive responses to an external force that is never fully within our neural and muscular control.

Going back to weightlifting vs. Power Lifting, the difference between them, besides performance, is the difference between tension and less tension of the musculature.

Muscle tension during exercise plays a pivotal role when it comes to triggering a metabolic growth and strengthening response. Weightlifting performed slowly with control creates more muscle tension than does power lifting, which employs stretch reflex, speed of motion and momentum to aid in the heaving or hoisting of a weight.

But the greatest tension of all is achieved with static muscle contraction – much more than even the most controlled weightlifting.

With this knowledge, it’s easier to understand why static exercise offers a significant advantage when it comes to the development of strength. An isometric contraction reinforces superior neurological control and engenders maximum muscle tension.

THE WILL

Conventional wisdom posits that exercise demands discipline and willpower. But as we’ve said before, that’s not entirely true. Whether or not people exhibit the will to exercise depends most of all on how it affects them personally.

Even then, of course, there will be the temptation not to exercise occasionally, but that would be the exception to the rule, provided that the method and protocol of the exercise is conducive, rewarding, and meaningful – all of which depends on having the knowledge beforehand to make an educated choice.

“Conducive” means the exercise is simple and time sparing.

“Rewarding” means the exercise leaves one feeling well and functionally fit.

“Meaningful” means the exercise achieves the desired objective.

Timed Static Contraction With Feedback (TSC) meets all three criteria, where other fitness regimens might be rewarding for the moment, but are more difficult, time consuming and lacking measurable results.

For example:

A typical weightlifting routine will occupy 90 minutes, 2-3 times a week. It demands elaborate skill learning and equipment know-how. The barbell setups can be rigorous and time-consuming in themselves.

A TSC session occupies 30-40 minutes weekly and is simple to learn and perform. Setting up equipment involves nothing more than adjusting. (More conducive)

Weightlifting can leave one feeling well but often leaves the participant sore and sometimes strained or sprained.

TSC leaves one feeling well and rarely sore and never strained. (More rewarding)

Progression from weightlifting is controversial because there are several variables that cannot be accounted for. Usually two variables are considered – repetitions and weight load – while speed of motion and duration are ignored because they are impossible to monitor reliably. So even with charting, which is rarely practiced, the selection of the weights from one workout to the next is a guesstimate at best.

A TSC session is free of variables because the method does not involve movement, and each exercise is timed identically from one workout to the next. Moreover, the work is measured and charted with the aid of a visual reader so that the objective may be evaluated to determine an accurate trend of progression. (More meaningful)

Under these conditions, it is hard to imagine having an urgent need for discipline and willpower because exercise has now become something that one wants to do.

THE PATIENCE

Most people who practice resistance exercise acknowledge the principle of progressive overload or at least have the idea that it’s necessary to push oneself a little further with every workout if they want to see positive changes in their physiques and functional abilities.

The notion of “pushing” supposes an increase in effort, which includes but is not limited to exertion, determination, and struggle.

As already mentioned, this simple premise has had centuries to prove itself. Therefore, the need to do more appears to be so ingrained that it has become almost an instinctive behavior for the majority who exercise.

However, what the “more” is exactly, is not well defined within the framework of conventional exercise. Is it a matter of performing more repetitions, lifting more weight, being more exhausted, or having more muscle soreness?

All or any one of these “stressors” might contribute to a strengthening effect. But which one is essential remains unknown: Maybe all of them under certain circumstances – or none of them.

If we’re interested in getting stronger without being overburdened by unnecessary expenditures of time and labor, we must try to identify the specific markers for progression that will directly affect a positive outcome.

The number one deficiency in this regard is our inability to know exactly how hard we are working while we are exercising. Most of the time we will work at a level of force and effort that is not quite hard enough. Yet the degree of effort is critical to success, so we might have greater confidence and motivation in knowing precisely what our optimal range of exercising intensity should be rather than guess.

Chiefly, we need to establish the minimum effort allowable, rather than assuming it must always be the maximal effort possible. In other words, it would be better to know how little work is actually necessary to build strength.

Personal trainers are in the thankless position of having to satisfy the temperaments of their clients while trying to exercise them hard enough to stimulate positive effects. The rule of thumb appears to be to urge trainees to work to as high a level of effort as they will tolerate before getting angry.

This is uncomfortable for everyone. But imagine, on the other hand, that a trainee’s level of effort could be viewed directly by the trainer? There would then be no need to question the integrity of the trainee or the judgement of the trainer.

If this is possible, it’s time to move beyond the “stone age” and embrace newer methods and technologies.

While there is equipment used in lab research to extrapolate oxygen consumption for steady state endurance work, these are not available in gyms. And in any case, there is no measuring device for effort per se.

And it’s also true for Timed Static Contraction With Feedback as well. However, there is a difference and a definite advantage to being able to continuously measure exercising force output in real time.

Of particular interest are the “fast-twitch” muscle fibers, because they are the largest and most difficult muscle cells to access – and in fact are rarely activated in most exercise programs because the exercising effort and intensity are usually too low.

It is the priority of Pure Exercise to recruit these very largest fibers and thoroughly exhaust them. This perfectly agrees with the premise of “high intensity” exercise because it has been shown by research and experience that acute intensity exercise accomplishes all that can be expected from exercise. However, it is essential that this type of exercise be performed with a high degree of effort. Fortunately, the redeeming factor for most people is that the exercising duration is extremely brief.

What is often not understood is that the brevity of the work depends entirely on reaching an appropriate peak of subjective effort. All too often people absolve themselves from the discomfort of peak effort by extending duration beyond the requisite time frame to, in effect, make the exercise easier and still call it “high intensity” when it’s actually not high intensity, but merely exhausting. As stated elsewhere, “exhaustion” does not define “intensity.” They are two different responses to two different types of physical exertion.

One may jog for hours to exhaustion without ever stimulating the fast twitch muscle fibers. On the other hand, sprinting as fast as possible for a minute will fatigue the largest muscle cells in addition to all the smaller fibers.

The first exercise is aerobic, or “steady-state,” while the second is anaerobic or “high-intensity.”

For those who believe that estimated weight charts are good enough to predict correct intensities, we state emphatically that there is no substitute for being able to see what an individual’s level of effort actually is during an exercise. That’s because effort and the accompanying exercising intensity level are fluid from moment to moment and may be influenced by numerous factors, including the current state of health and emotional outlook.

So how do we figure this out? The honest answer is we can’t – or not completely. The enlightened trainee, knowing what needs to be done, should be willing to commit to the necessary hard work with or without the motivational inspiration of a trainer or the assistance of any technology.

Having said this, a system and method can be implemented to establish a reliably accurate exercising intensity level that is more or less independent of one’s transient subjective feelings.

The system is constructed from what is known about functioning biology, ATP energy production, and the mechanics of muscle contraction. The method describes how the parts of the system can be made to work together.

With ALL physical exertion there is an inverse relationship between one’s effort and the amount of force being produced.

Force is expressed by thousands of muscle cells manufacturing energy and mechanically contracting the muscle tissue.

Effort is experienced as increasing discomfort from that force coupled with dwindling blood oxygen as the pulmonary cardiovascular system tries to keep up with the quickening metabolic processes in the working muscles.

Whether one is lifting weights or tensing muscles isometrically, the biology is the same.

The longer force is produced, the more discomfort is felt. How long it takes to reach the tipping point of dysfunctional muscular fatigue depends on the amount of force being spent for a given span of time.

So, the two factors most responsible for effort and intensity is the specific amount of force and the specific duration of that force.

With this understanding, it is practicable to formulate an accurate exercise intensity, provided the method of exercise has the fewest possible variables. That excludes all modes of exercise except one: Timed Static Contraction – the only method of exercise that involves just force and duration.

With weightlifting, speed of movement and range of movement can never be precisely replicated. Each time a lift goes a little higher or lower, or a little faster or slower, both force and duration are altered. This creates additional inconsistencies that cannot be reconciled.

For our purpose we need maximum constancy and consistency. Having just force and duration to consider simplifies the calculation and makes it feasible to anticipate an exercising intensity.

The first step is to establish the timeline of an exercise. It must be based on how long it takes to generate an anaerobic state. For it is during that special metabolic condition that muscle fatigue and peak effort coincide.

Anaerobic metabolism occurs optimally within 3 minutes, provided that the exertion of force is appropriately intense. If not, the metabolic pathways will naturally shift to aerobic energy production. Therefore, TSC is “timed” to foster an anaerobic state with peak effort within a total duration of 90 seconds – of which the highest force is concentrated within a sixty second duration. This congruency of duration, force, and anaerobic response guarantees activation of the fast twitch muscle fibers.

Without visual feedback none of this would be possible. It is how technology can assist the processing of exercise. And it’s not even “high tech.” It is as simplistic as using strain gauges and a reader – the standard components of an ordinary weight scale. For example, if we push or pull on the handles of a TSC machine, a digital reader will show “0” rising to higher numbers displayed as lbs.

Each exercise will test for the highest weight that a subject can produce by muscle exertion without undue discrepancies of form or performance. Such details provide all the information needed to see the exercising intensity moment to moment.

Usually, the better a person’s constancy of form and number, the greater the strength. Stabilization of the body is the critical factor. This reflects back to the early teachings of Sandow and other great strongmen. The more muscular control one can demonstrate, the greater may be the strength, but also the greater will be the effort, intensity, and overall effectiveness of the exercise.

When performance and number destabilize, and can no longer be controlled, the onset of muscular weakening or fatigue begins. If this happens early in the set, the target force is prescribed too high. But if muscle fatigue and effort peak at the very end of the set, we will have successfully calculated an accurate target force and intensity level.

Once this baseline is established, workouts can progress with no need for reevaluation. However, with every workout the same details of performance must be scrutinized, because as stated before, exercising intensity is always volatile and reactive to passing influences.

Yet regardless of transient influences, which depends on the unique constitution of every individual, the TSC method and system itself has been shown to be reliably accurate. It removes much of the guesswork that plagues conventional exercise and frees the individual to concentrate more exclusively on the finer details of performance that will determine how successful an exercise will be.

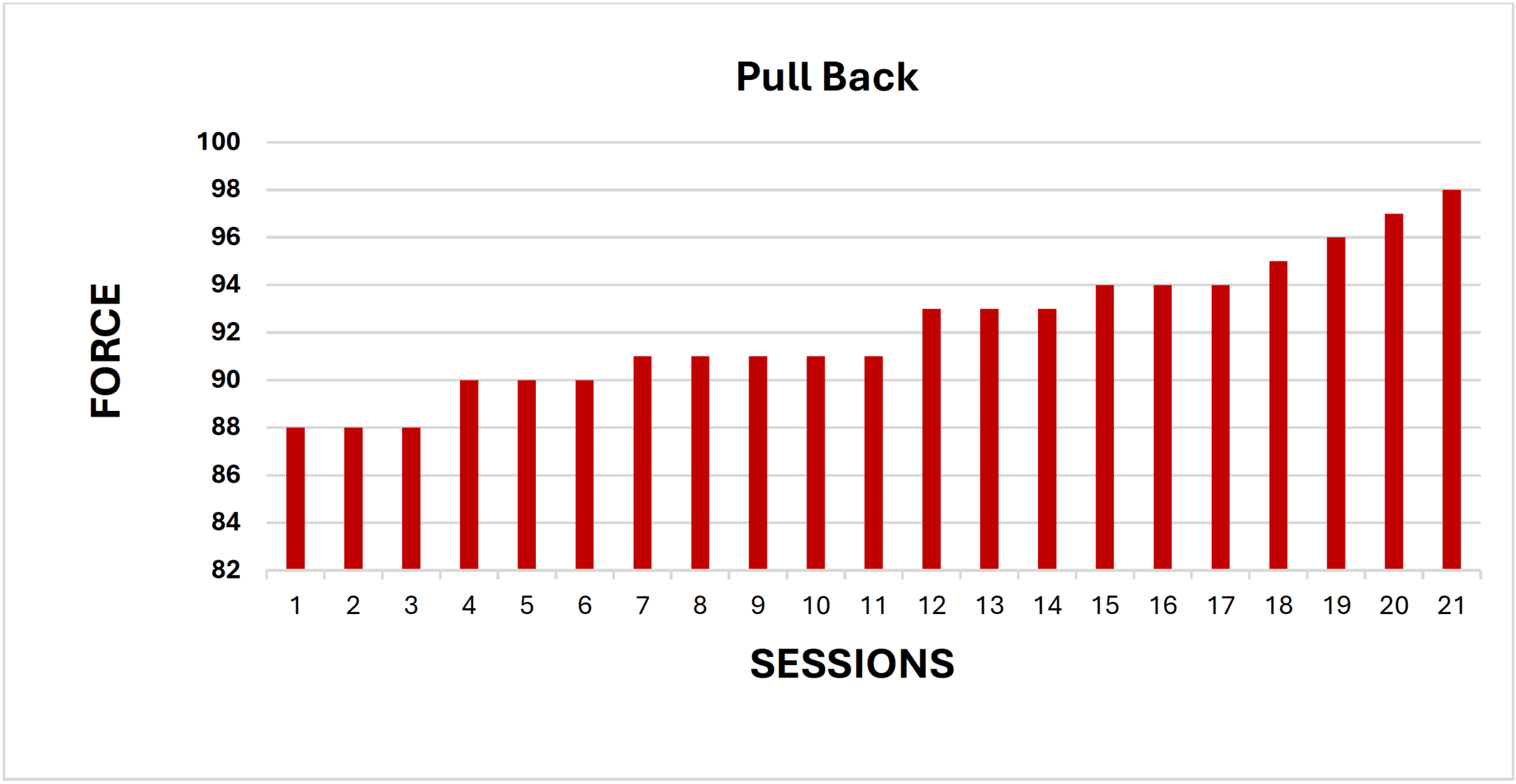

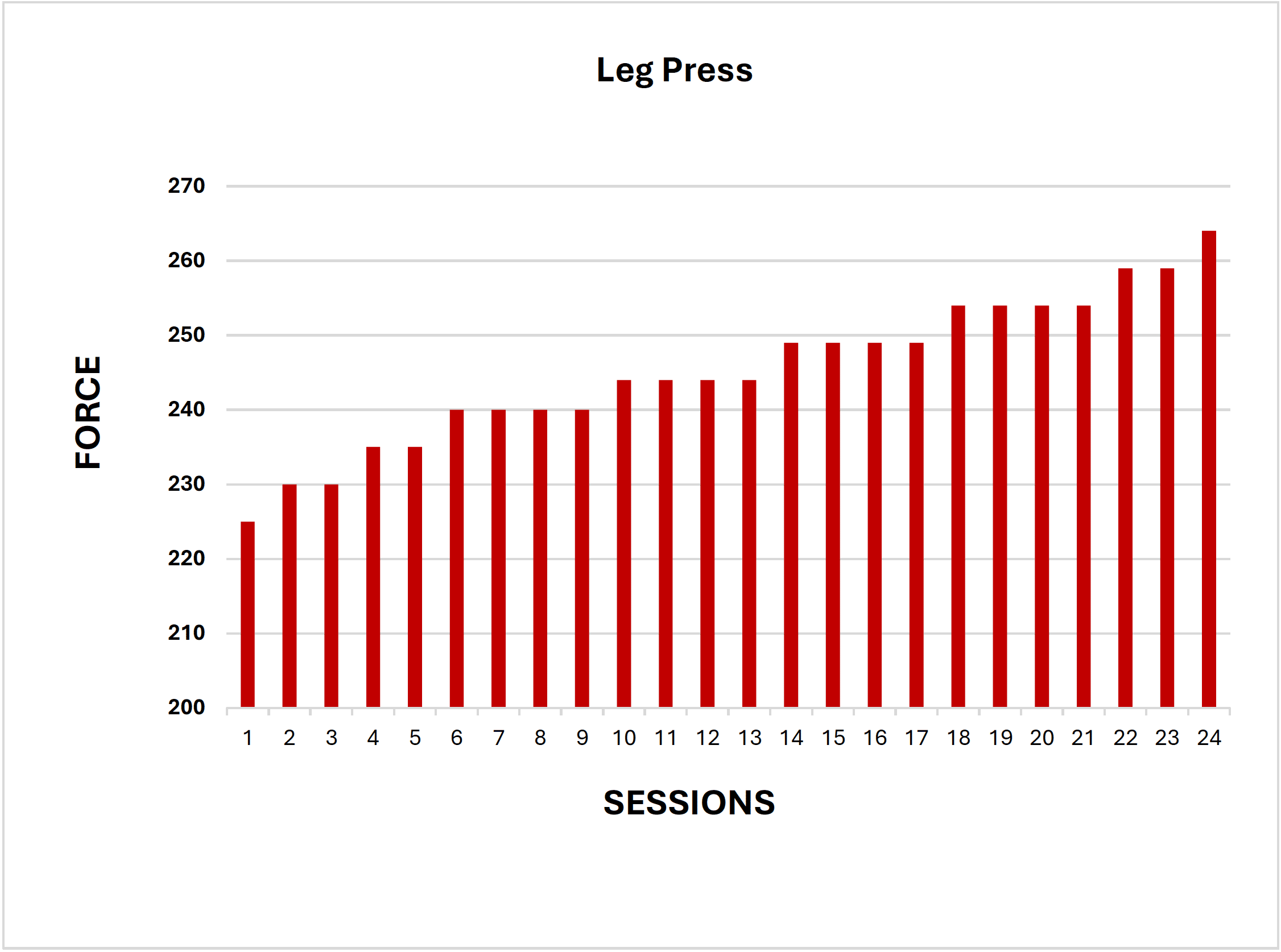

The accumulative results of this exacting work is reviewed on a TSC progress report. It is a simple matter of collecting all target numbers over the months to view the trend of progression. This is where the idea of patience must be emphasized.

Physiological adaptation has its own pace, depending on age, gender, and individual determination. The common mistake with strength training is to make assumptions about the time it should take to develop or grow muscle tissue. Impatience is mostly responsible for all the setbacks and injuries at the local gyms. Few are willing to accept reality, probably because the public has been hyped for decades.

Again, we must respect the natural human adaptive process as our model and not allow our fantasies to be taken seriously. Reality speaks for itself; it one has the patience to wait and see what actually happens…

Whether we like it or not, strength increases cannot occur faster than natural processes will allow. Physical adaptation of any kind is better achieved with small improvements over time rather than pushing large changes too rapidly.

Progress graphs reveal a trend line of incremental adaptations that have been stimulated by timed static contraction workouts performed weekly.

“Force” numbers are the same as weight numbers. And just as in weightlifting, an increase in weight / force signifies an increase in strength.